Google found guilty of illegal exclusive dealing

10 initial observations regarding Judge Mehta's decision in United States v. Google

As expected, Google lost its antitrust lawsuit United States v. Google in first instance. Below are 10 initial observations about yesterday’s decision, what’s next and why the company could ultimately prevail on appeal.

1

Judge Mehta from the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia released a 286 pp. strong opinion yesterday in which the court held that a) the markets for general search services and general search text ads are relevant product markets, b) Google has monopoly power in those markets (demonstrated through indirect evidence in the form of 89.2% share in the market for general search services and 88%+ share in the market for general search text ads, c) Google’s distribution agreements are exclusive and have anticompetitive effects and d) Google has not offered valid procompetitive justifications for those agreements.

In short, Google’s defense strategy to highlight healthy “competition for the contract”, cross-market benefits and the fact that its default deals “allow the browser’s search functionality to work effectively out of the box” were not accepted as procompetitive justifications by the judge.

2

With this decision, the liability phase of the lawsuit ends. Next up is the remedy phase. The same court will hear proposals from both Google and the DOJ what kind of remedies are appropriate to end the illegal practices. Both parties must propose a schedule for proceedings regarding the remedy phase until September 4.

3

It was clear from the beginning that whichever side would lose this lawsuit would appeal as the stakes for both sides are too high. Directly after Google found out that it lost, it issued a statement in which Kent Walker said: “The court’s decision recognizes that Google offers the best search engine but concludes that we shouldn’t be allowed to make it easily available” and that they “plan to appeal”. Google will also ask to delay the remedy phase while it’s appealing the decision and we will get an update on whether this will be granted or not during the next weeks.

The case will next go up to the DC Circuit and could ultimately be escalated up to the Supreme Court.

4

Regarding why Google was found guilty: The DOJ filed United States v. Google LLC under ii) section 2 of the Sherman Act. To win its case, it needed to show that 1) Google possesses monopoly power in properly defined markets AND 2) that Google engages in exclusionary or predatory practices to maintain or enhance that power.

As I stated above, the court found that the DOJ has proven that Google has monopoly power in two relevant product markets: general search services and general search text advertising. On the other hand, although the court recognized a separate market for search ads, it found that Google did not have monopoly power in that market and it also rejected a separate general search ads market.

The next step in the analysis then was to determine whether Google has engaged in exclusionary practices within the markets of general search services and general search text advertising. Here, the DOJ always focused it case on the search distribution contracts – primarily with Apple. In essence, the lawsuit is an exclusive dealing case in which the DOJ successfully convinced the judge that Google’s default deals lead to a substantial foreclosure of search engine competitors in the competition for distribution.

5

To win a substantial foreclosure case, it's usually required to prove that a monopolist has foreclosed at least 40% of the relevant market with long-running distribution contracts and that the challenged agreements threaten to reduce output or raise prices. With the Google contracts in question locking up “half of the market for search and nearly half of the market for general search text ads”, the court decided that the default deals illegally protect Google’s dominant position and shield it from meaningful competition. Google counter-argued that before a device manufacturer decides to distribute Google as its preferred search service there is always healthy “competition for the contract” and that it has won the defaults through competition on the merits as opposed to exclusionary conduct.

This argument didn’t sit well with the court and it ruled that “competition for the contract” is no defense here. It further found evidence of market stasis, e.g. in the last 22 years only once has a rival dislodged Google as the default GSE, and in that case, Mozilla switched back from Yahoo to Google three years later. Despite the courts assessing the contracts as illegal, it had to acknowledge multiple times that Google “has long been the best search engine, particularly on mobile devices. Nor has Google sat still; it has continued to innovate in search. Google’s partners value its quality, and they continue to select Google as the default because its search engine provides the best bet for monetizing queries. Apple and Mozilla occasionally assess Google’s search quality relative to its rivals and find Google’s to be superior.”

6

During the appellate process, it is going to be interesting whether higher courts will derive the same conclusion as the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. Contemporary U.S. antitrust analysis has long recognized that “competition for the contract” can also benefit consumers. Court precedents under the influence of the Chicago School established that “in many circumstances exclusive-dealing arrangements may be highly efficient – to assure supply, price stability, outlets, investment, best efforts or the like – and pose no competitive threat at all”. Former rulings also held that “competition for the contract is a vital form of rivalry, and often the most powerful one, which the antitrust laws encourage rather than suppress.” Keep in mind that the high courts often are in the hands of conservative judges whose entire self-perception and career achievements rest on the laurels of the Chicago School. The Supreme Court is considered the most business friendly which makes it difficult for disputable cases to prevail all the way up the system.

7

In terms of remedies: everything is on the table! The list goes from behavioral to structural relief measures. Judge Mehta will look forward to end the exclusive dealing contracts but given his more cautious nature, a draconian break-up seems less likely as of today. The DOJ originally called for “structural relief as needed to cure any anticompetitive harm”, but towards the end of the trial it also entertained a choice screen as a remedy. This measure would forbid Google from paying for default status but allow it to pay for inclusion in the choice screen. Smaller rivals like Bing could still bid for default and Apple then had to choose which option it prefers. The DOJ and the court could draw inspiration for such a remedy from the European Commissions’ precedent after its 2018 decision against Android. One remedy in the aftermath of that case was that Google as the monopolist was no longer allowed to offer OEMs a revenue share for exclusive pre-installation of Google Search in Europe. Bing or Yahoo, however, may still bid for exclusive pre-installation and defaults. Google may offer a revenue sharing agreement for non-exclusive pre-installation without default status, in which case device manufacturers must show a choice screen during the initial setup of a new Android device. However, such a remedy would have a catch in United States v. Google: it would probably need to be a proactive offer by Google and its partners as the device manufacturers Apple or Samsung are not defendants in this case.

8

In the opinion released yesterday, an interesting passage on p. 34 reads that in 2020 Google’s internal modeling team projected that it would lose between 60–80% of its iOS query volume should it be replaced as the default GSE on Apple devices, which would translate into net revenue losses between $28.2 and $32.7 billion, which again translate into 15.4% - 17.9% of Alphabet’s total F2020 revenue (and it expected over double that in gross revenue losses, see below).

At first glance, those numbers seem a bit off to me and I can’t really square them with the fact that gross Google Search revenues on all Apple devices amounted to $50 bn in 2021 and Google paid Apple $18 bn in 2021 for default status in form of a revenue sharing agreement which amounted to 17% of Apple’s 2021 operating profit. The payments to Apple subsequently went up to $20 bn in 2022.

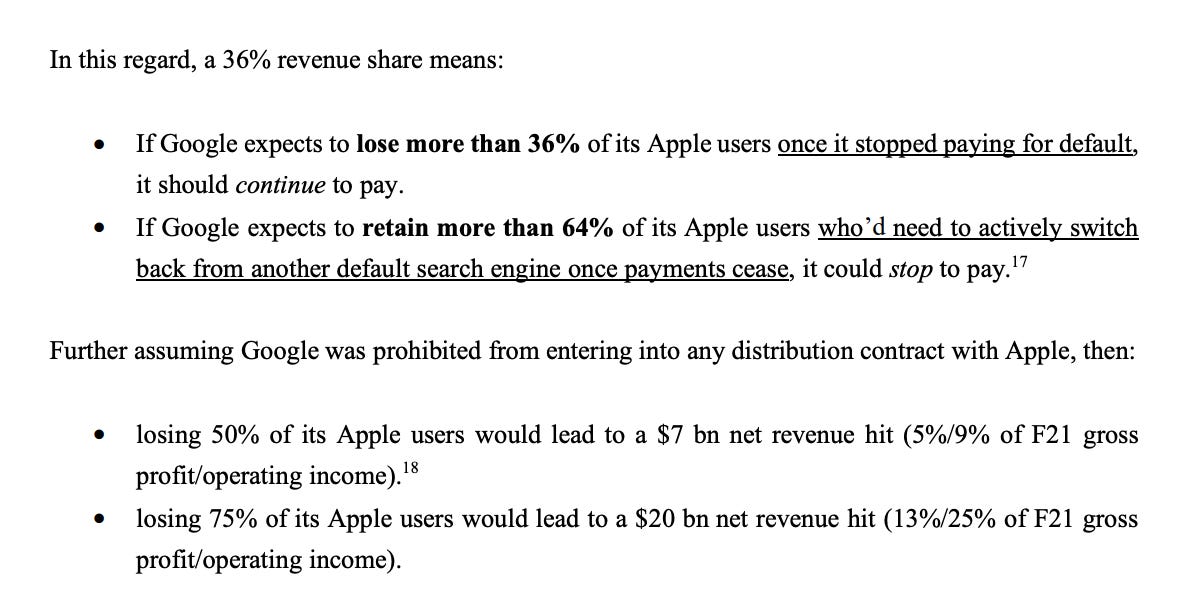

In a scenario where Google would be banned from entering into any distribution deal with Apple, I still think a more reasonable estimate is to assume the company could lose profits in the range of 9-25% of its operating income as I have written in April (see below).

9

I still think a remedy like the one just described under point 8 would be antithetical to the gist of antitrust. If Apple is indeed the kingmaker in search, then allowing Bing to pay for distribution but not Google means the government would pick winners and losers. Therefore, a more likely outcome when we discuss choice screens during the next months could lead to the following outcome: Google could pay Apple an unchanged amount for nonexclusive distribution through a choice screen. We already have this remedy in Europe on Android devices signed off by the EC and 96% of EU Android users actively choose Google on their choice screen. This kind of remedy shouldn’t pose a major threat to Google’s economic profile.

However, margins could come down a bit as it was indicated during trial that “Google’s revenue share payments to Android partners in Europe increased after the introduction of the choice screen as Google took steps to stave off the threat that newly emboldened rivals might otherwise “secure full search exclusivity” on Android phones.”

The last point has the added charm that it makes it much easier for the DOJ and the judge to argue how this version of a choice screen increases consumer welfare as distributors would take in more money from Google that could be passed through to consumers in form of lower device prices. Albeit this benefit again comes down to the topic of cross-market balancing, which, as seen again yesterday, some courts have considered in certain instances while others have not

10

Lastly, the remedy phase could have a significant potential impact on Apple’s bottom line. As soon as Google would be excluded from “competition for the contract”, the next best bid (from Bing) would drop materially. For illustrative purposes, if Apple wanted to regain a default deal revenue shortfall of $10 bn solely through annual iPhone sales in the range of 200m devices, iPhone prices for consumers would need to go up by ~$50.

If Apple wanted to prepare for a worst case scenario and start building its own search engine, Google estimated it would cost the company more than 40% of its total R&D budget (see below).

Money wouldn’t be an issue here and Apple creating its own search engine was definitely within the realm of possibility some years ago. However today, with U.S. regulators attacking Apple’s integration between hardware and software services and European regulators banning self-preferencing outright with the DMA, I have severe doubts regarding the viability of such an undertaking.

These are my 10 initial thoughts on where we are at right now. So far, no surprises. Things will get more interesting as soon as the appeal reaches the DC Circuit.

[end of post]

If you don’t want to miss anything, you can follow me on Twitter: @patient_capital

To learn more about the investment fund I advise or access my previous annual letters to investors you can click the button below.

This document is for informational purposes only. It is no investment advice and no financial analysis. The Imprint applies.