Book Review: "The Nvidia Way - Jensen Huang and the Making of a Tech Giant"

What I Read and If I Would Recommend It

What I Read

From time to time I get asked what books I’d recommend. Therefore, I infrequently post about some of my latest reads — both within and beyond the field of investing.

You probably became aware of this Substack for its long-form business model breakdowns like:

In contrast, the book reviews will be rather short and not contain too many spoilers. To learn more about the investment fund I advise or access my annual letters to investors you can click the button below.

"The Nvidia Way - Jensen Huang and the Making of a Tech Giant" by Tae Kim

The last book I read was “The Nvidia Way - Jensen Huang and the Making of a Tech Giant” by Tae Kim.

The book traces the origins of chipmaker NVIDIA, which became the most valuable publicly traded company in mid-2024, surpassing $3T in market cap and placing it in the same league as tech giants like Microsoft and Apple.

NVIDIA came from humble beginnings. It was founded in 1993 at an East San Jose Denny’s restaurant by three men and got off to a rocky start. Tae Kim’s book highlights several of NVIDIA’s early near-death experiences — moments that are often forgotten when success stories are told from the end to the beginning, rather than the other way around.

As for NVIDIA, its meteoric rise over the past 32 years is inextricably linked to its CEO and co-founder, Jen-Hsun "Jensen" Huang. Jensen has held the top job at NVIDIA for 32 years, and with Warren Buffett stepping down as Berkshire’s CEO at the end of this year, Jensen will soon become the third longest-serving CEO of any S&P 500 company. The only two with longer tenures are Stephen Schwarzman (39 years at Blackstone) and Leonard Schleifer (37 years at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals).

Jensen was born into a working-class Taiwanese family in 1963. At one point, his father found work in Thailand, and the family relocated with him. Jensen’s mother taught him and his brother English, and when political unrest hit the country, the two boys were sent to the U.S. to live with their aunt and uncle.

It had always been their parents’ dream to send the boys to an American prep school and allow them access to a higher education than they themselves had received. After selling nearly all of their belongings, they enrolled Jensen and his brother at the Oneida Baptist Institute in Kentucky. However, what the family believed to be a prep-school was in fact a reform school for troubled and delinquent youth.

During his first months on campus, Jensen was beaten up regularly. He would later describe his years at Oneida Baptist as formative and character-building, particularly in terms of overcoming fear and discomfort. Jensen’s work experience also began at Oneida Baptist, where he was assigned to clean the bathrooms of his three-story dormitory. At age fifteen, he took another job at a Denny’s diner in Portland, again cleaning bathrooms and washing dishes. He later joked that he “did more bathrooms than any other CEO in the history of CEOs”.

As he made his way into the Oregon State University in Corvallis, Jensen developed an interest in computers — partly because he had fallen in love with video games. After graduating, he interviewed with AMD and joined the company as a chip-designer. At the same time, he pursued a master’s degree in electrical engineering at Stanford.

When he later joined LSI Logic, an ASIC supplier to other semiconductor companies, he took on the role of a chip designer and was assigned to work with two engineers from Sun Microsystems, Curtis Priem and Chris Malachowsky. These two men would later become his co-founders at NVIDIA.

At Sun, Curtis and Chris worked on a graphics card, called the GX, for their employer’s professional workstation, the SPARCstation. In the late 1980s, Curtis was the principal architect of the GX, which should enable 3D modeling and design visualization at a time when the leading graphics standard (EGA, see below) allowed only a resolution of up to 640x350 pixels and 16 different colors.

Priem was an early-learner who taught himself how to code in high school. He immediately put his skills to use by writing computer games. When he and Chris built the GX, he considered one off the best demos for the card’s enhanced capabilities — which included a resolution of up to 1152x900 pixels, 256 colors, and instantaneous scrolling of text for the first time — was to revisit a shelved gaming project he had been waiting to finish. That project was a realistic flight simulator game called Aviator.

Prior to the GX, graphic cards were unable to render the complex physics of an aircraft in flight. But with the GX, Priem finally had the means to complete Aviator and showcase it on the SPARCstation. To my surprise, there’s still a video online of an early version of Aviator running on the SPARCstation, which you can watch here.

The game, the GX and Jensen’s management of the outsourced production of the chip at LSI were all great success stories, and all three men received promotions. However, as Sun Microsystems grew, its agility and startup-like culture diminished, much to the frustration of Curtis and Chris. Curtis wanted to build a successor to the GX for Windows PCs as soon as possible, but due to the bureaucracy at Sun, Curtis and Chris decided to venture out on their own. Together with Jensen, they founded NVIDIA in 1993 (all three founders are shown further below).

To do so, they raised $2m in a Series A — half of it from legendary Sequoia co-founder Don Valentine, who reportedly told Jensen before writing the check: “Against my better judgement, based on what you just told me, I’m going to give you money. But if you lose my money, I will kill you”.

Pages and Length

Before we get to an excerpt of what the book is about and my verdict below, let’s take a brief look at its specifications:

pages: 261

Investment Book: partly (business biography)

language: not overly technical and easy to read

time to finish: I read the first half during a 1 week holiday and the rest at home

Excerpt of What the Book Is About

In total, Tae Kim structures his book into four parts:

PART I: The Early Years (Pre-1993)

Pain and Suffering

The Graphics Revolution

The Birth of NVIDIA

PART II: Near Death-Experiences (1993-2003)

All In

Ultra-Aggressive

Just Go Win

GeForce and the Innovator’s Dilemma

PART III: NVIDIA Rising (2002-2013)

The Era of the GPU

Tortured into Greatness

The Engineer’s Mind

PART IV: Into The Future (2013-present)

The Road to AI

The “Most Feared” Hedge Fund

Lighting the Future

The Big Bang

Especially the chapters about NVIDIA’s several near death experiences and severe drawdowns on its journey to become the world’s most valuable publicly listed company stuck with me. Another standout chapter is “NVIDIA Rising (2002-2013)”, which recounts the story how scientists hacked NVIDIA’s GPUs to compute non-graphics computations on graphics cards.

This hacking sparked the so-called GPGPU (General Purpose computing on GPUs) movement, which culminated in NVIDIA launching its CUDA software platform in 2006. As Jensen and his colleagues realized the potential of running non-graphics tasks on GPUs — which have more cores compared to CPUs and can process massive amounts of data simultaneously rather than sequentially — they invested aggressively in what today serves as the backbone of the Gen AI revolution.

Near-Death Experiences

After co-founding the company, Curtis quickly fleshed out a design concept for NVIDIA’s first graphics chip for Windows PCs. He branded it the NV1 chip and bet on a new technically superior rendering standard called QTM, which used quadratic texture mapping instead of the market’s triangle-based standard. Additionally, Curtis aimed to introduce a proprietary audio format and build a combined graphics and sound card.

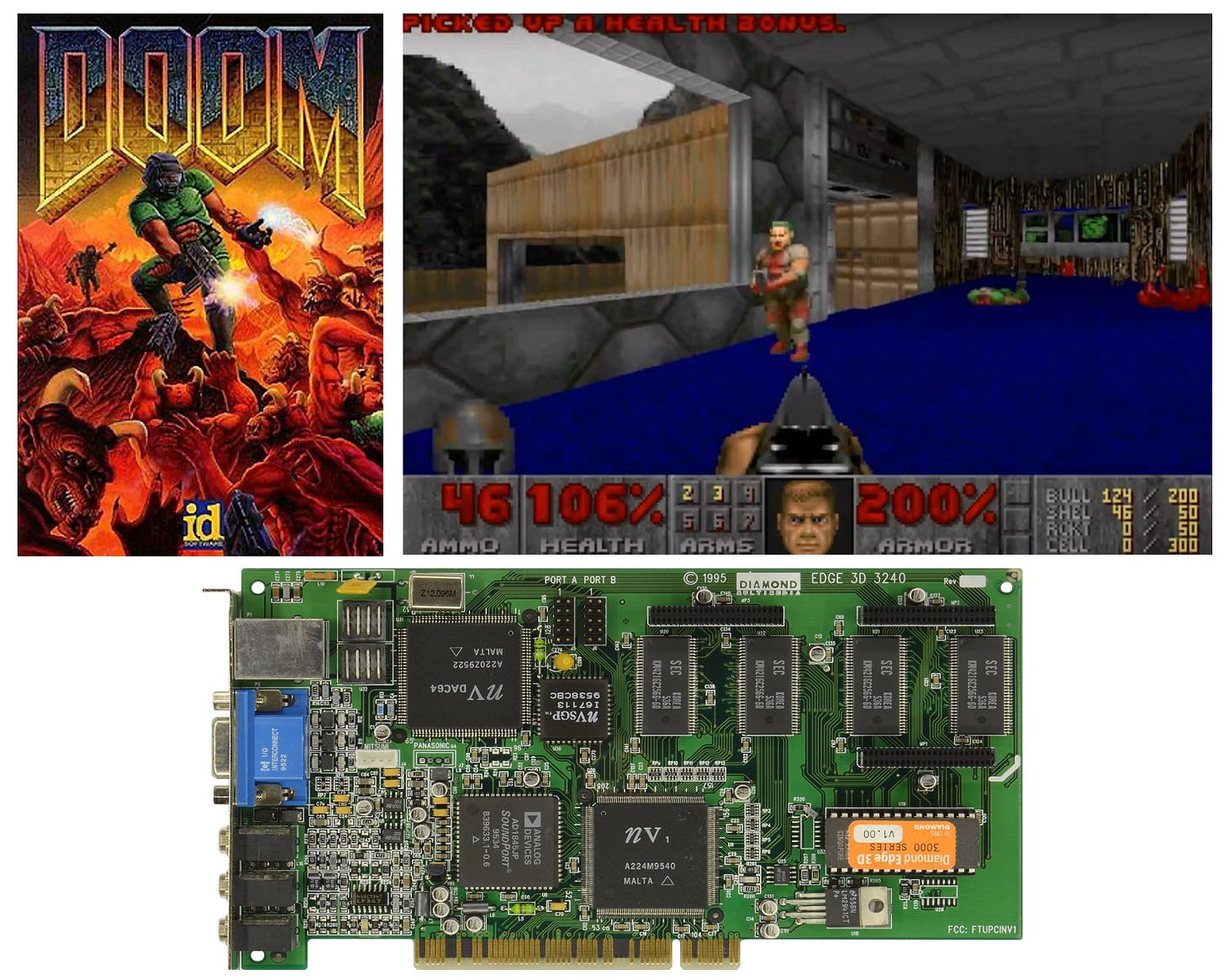

The NV1 was announced in May 1995, and Jensen, Curtis, and Chris expected it to be a huge success due to its advanced capabilities — on paper, at least. However, the reality check came swiftly when consumers installed NV1s in their PCs to play the most popular game at the time — DOOM — which single-handedly sealed the product’s fate:

“At the time of the chip's launch, DOOM was the most popular game in the world: its kinetic visuals and gruesome, fast-paced combat were unlike any other gaming experience ever produced. This was in large part due to the technical wizardry of John Carmack, the game’s designer and co-founder of its publisher, id software.

Carmack built the game using the 2D Video Graphics Array (VGA) standard and leveraged every hardware-level trick he knew for maximum visual impact. Priem had been sure that most game designers would switch to the NV1’s 3D-accelerated graphics and leave VGA behind. So the NV1 chip only partially supported VGA graphics and relied on a software emulator to supplement its VGA capabilities – which resulted in slow performance for gamers playing DOOM. Even DOOM’s iconic soundtrack and sound design didn't work properly on the NV1.

I was a hard lesson on the value of backwards compatibility and the dangers of innovating for innovation's sake. NVIDIA’s card which was supposed to push the boundaries of the graphics industry couldn’t keep up with the world's most popular game. It was sunk by a lack of truly compatible games and the ongoing support from most game makers for inferior, though widely adopted, technical standards.”

NV1 sales flopped! Most customers who bought the graphics card during the holiday season returned it immediately. This episode brings to mind other examples of advanced technologies that failed due to a lack of ecosystem support and the stickiness of inferior but more widely adopted standards — like Betamax vs. VHS.

NVIDIA now needed a quick win with its NV2 chip for Sega’s upcoming gaming console, the Dreamcast. However, after the NV1 fiasco, Sega decided not to bet on NVIDIA as a startup any longer and paid them only a milestone payment of $1m, which went almost entirely into R&D for the NV3. Without the expected revenues from selling lots of NV1 and NV2s, NVIDIA faced its first severe liquidity crisis. Jensen had to shrink the company by over 60%, cutting headcount from more than a hundred employees to forty.

If the situation wasn’t tense enough, by 1996 a formidable new competitor had emerged: 3dfx, with its upcoming lineup of Voodoo graphic cards. When id Software released Quake, a successor to DOOM, it once again landed a hit in the first-person shooter genre — this time rendering everything in real-time 3D and allowing online multiplayer. The game became the killer app for the Voodoo 1 and sales of 3dfx exploded, propelling the company from strength to strength.

Meanwhile, cash-constrained NVIDIA had no competitive answer to the Voodoo 1 and was still developing the NV3. At this point, 3dfx briefly considered making an acquisition bid for their weakened competitor, which would have drastically altered NVIDIA’s fate. However, with only nine months of runway left before bankruptcy, 3dfx opted to simply hire away NVIDIA’s best engineers if the NV3 flopped.

Internally, Curtis, Chris and Jensen now abandoned their previous design philosophy of pushing new proprietary technologies and instead prioritized maximum speed and compatibility with existing standards. To signal this change externally, they renamed the NV3 to RIVA 128, which was released in 1997 and outperformed the Voodoo 1 on every benchmark. Within four months of the chip’s release, NVIDIA shipped more than one million units and captured 20% of the PC graphics market. This success not only allowed the company to survive its first near-death experience but also enabled it to announce its first profitable quarter, four years after its founding. However, the cosy feeling didn’t last long.

Just a year later, in 1998, Intel announced its i740 graphics chip. As the dominant CPU maker for nearly all Windows PC, Intel had a strong hand to sway PC manufacturers into buying their product instead of a competitor’s, and NVIDIA quickly felt its sales pipeline dry up. Jensen was under no illusion what the i740 meant and declared at an all-hands meeting:

“Make no mistake. Intel is out to get us and put us out of business. They have told their employees and they have internalized this. They are going to put us out of business. Our job is to kill them before they put us out of business. We need to go kill Intel.”

Jensen wanted to outcompete the i740 with a much more powerful chip, the RIVA TNT. However, making its debut and passing quality tests on time became a serious challenge. NVIDIA was once again only weeks away from insolvency when it negotiated emergency bridge financing from its three largest customers. Jensen sweetened the deal by offering the option to convert the loans into equity at 90% of the eventual IPO price. This funding kept NVIDIA afloat while they completed testing the RIVA TNT and successfully fended off the threat from Intel.

In 1999, NVIDIA went public and also released its biggest product breakthrough yet: the GeForce 256. It was the first product NVIDIA labeled as a GPU. The GeForce 256 offloaded complex geometry math calculations from the CPU, allowing developers to create more detailed gaming environments. In hindsight, it also unintentionally laid the groundwork for the GPGPU movement and today’s Cambrian explosion in AI.

The Dawning AI Revolution

While you might have already heard of NVIDIA’s founding story and its early products, Tae Kim’s chapter on “NVIDIA Rising (2002-2013)” does a great job bridging the evolution of graphics chips from in-game rendering to their increasing application in academic and scientific research.

NVIDIA released the GeForce 3 in 2001 as its first GPU with programmable shaders. These shaders gave game developers the ability to write custom programs running on the GPU to control how every pixel, shadow or reflection appears on screen. While it took some time for developers to learn how to write code for custom shaders, by around 2004, programmable shaders became widely adopted to customize the look and feel of games. From this point, a fascinating story unfolded about how these new capabilities escaped their original use case and made their way into academic research. This story centers on a PhD student who had a deep interest in… clouds:

“One of the earliest references to the technology that would eventually turn NVIDIA into a trillion-dollar company was in a PhD thesis about clouds. Mark Harris, a computer science researcher at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, wanted to find a way to use computers to better simulate complex natural phenomena, such as the movement of fluids or the thermodynamics of atmospheric clouds.

In 2002, Harris observed that an increasing number of computer scientists were using GPUs, such as NVIDIA’s GeForce 3, for nongraphics applications. Researchers who ran their simulations on computers with GPUs reported significant speed improvements over computers that relied on CPU power only.

But to run these simulations required computers to learn how to reframe nongraphics computations in the terms of graphical functions that a GPU could perform. In other words: the researchers had hacked GPUs.

To do so they utilized the GeForce 3’s programmable shader technology — originally designed to paint colors for pixels — to perform matrix multiplication. This function combines two matrices (basically tables of numbers) to create a new matrix through a series of mathematical calculations. When the matrices are small, it's easy enough to perform matrix multiplication by use of normal computational methods. As matrices get larger, the computational complexity required to multiply them together increases cubically – but so does their ability to explain real-world problems in fields as diverse as physics, chemistry and engineering.

“Really the modern GPU, we kind of stumbled onto,” said NVIDIA scientist David Kirk. “We built a super powerful and super flexible giant computation engine to do graphics because graphics is hard. Researchers saw all that floating-point horsepower and the ability to program it a bit by hiding computation in some graphics algorithm.”

What’s intriguing about this revolutionary idea to use GPUs for non-graphics work is that there was no “light bulb moment” from anyone inside NVIDIA who foresaw the new computing paradigm with strategic clarity. Instead, as quoted above, executives “stumbled onto it,” while researchers in academia independently explored what was adjacently possible in their fields as they looked for new ways to solve complex math problems using GPUs instead of CPUs.

More often than not, innovations happen exactly like that. Another great author, Steven Johnson, did a fantastic job demystifying the “light bulb moment” — a concept that has become synonymous with the heroic stories we like to tell each other about visionary founders inventing a new thing in a sudden burst of inspiration. I’ve previously written a review of Steven’s book “How We Got to Now” (linked below).

My remark that NVIDIA “stumbled” onto the GPGPU business isn’t meant to take any credit away from Jensen or the rest of the executive team. As soon as they recognized the potential in what Mark Harris and others had originally hacked their GPUs for, they aggressively invested in parallel computing. One result of these investments was the release of CUDA in 2006.

Before CUDA, programmers had to trick shaders into thinking their math was part of an image-rendering task. They also had to use NVIDIA’s proprietary language, Cg, instead of general-purpose languages like C or C++. CUDA changed that. Since then, not only graphics programming specialists but also scientists across disciplines have been able to harness the GPU’s computing power to solve problems in deep learning and simulations that traditional CPUs couldn’t handle.

In 2008, management became vocal about its ambition to expand aggressively beyond graphics into GPGPU and a data center business. At NVIDIA’s analyst day, Jensen expressed his belief that these new segments would unlock an additional TAM of $6B within a few years, up from near-zero at the time. To prepare for the anticipated demand, NVIDIA decided to make all its GPUs CUDA-compatible, to the temporary detriment of its gross margins, which fell to 35% in FY2010 compared to 70%+ today.

In hindsight, NVIDIA was clearly on the right track. However, Tae Kim does a great job recounting how, at the time, Jensen’s vision and the company’s plan to target an obscure corner of academic and scientific computing was mostly met with skepticism:

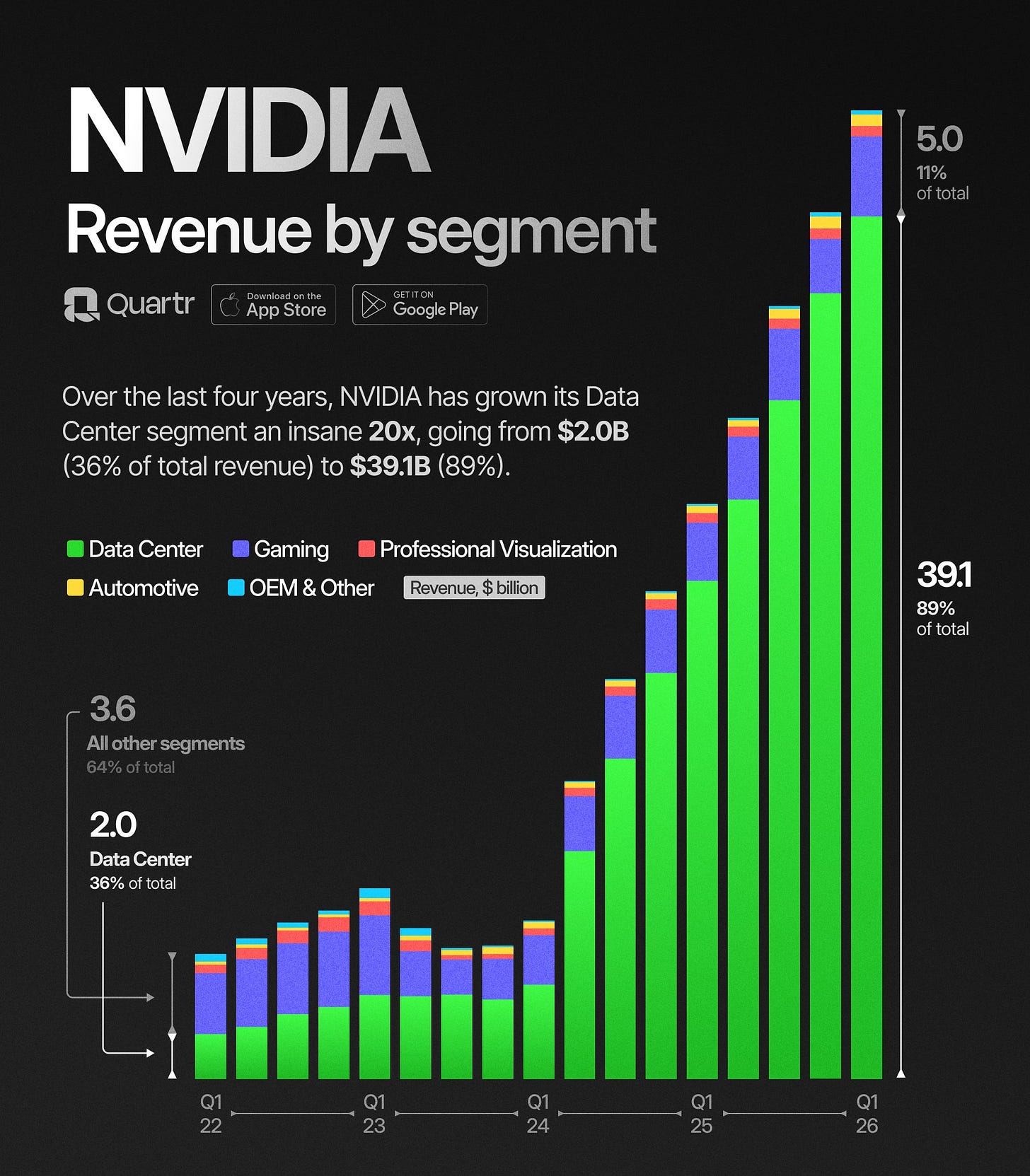

It would take another decade until NVIDIA’s surging data center orders silenced the last skeptics of its push into the AI infrastructure business. After the release of ChatGPT in November 2022, expectations for the company’s topline had been steadily rising, but it was NVIDIA’s Q1 FY2024 earnings release on May 24, 2023 that marked one of the most remarkable earnings announcements in recent stock market history.

The company reported quarterly revenue of $7.19 billion, up 19% from previous quarter, data center revenue of $4.28 billion, but then — most stunningly — a second quarter fiscal 2024 revenue outlook of $11.0 billion, more than 50%(!) above the prior Street estimate of $7.2 billion. The stock surged another 24% that day.

Such a large expectation beat at this scale was unprecedented even for tech stock veterans like Gavin Baker, ex-Fidelity and now CIO of Atreides Management:

The rest of course, is history. The momentum of FY24 didn’t slow down, and analyst consensus now sees almost $250B in FY27e revenue — nearly a tenfold increase compared from the $27B recorded just five years ago. Meanwhile, its data center segment revenue has grown by more than 20x (see below).

Over the last 10 years, the stock has become a 250-bagger, compounding at an almost unbelievable 74% p. a. However, as I point out in my concluding remarks below, the journey to achieve this miracle result wasn’t smooth sailing at all.

What Are My Main Takeaways From the Book?

For me, there are three main take-aways:

Tail events drive everything. The history of every ultimately wildly successful startup is filled with tail events — moments where small variations would have led to vastly different outcomes. NVIDIA is no exception and could easily have ended up bankrupt or acquired multiple times.

Experiencing volatility is the price to pay for attractive long-term returns. I have said it many times — such as in my 2020 Investor Letter — and I’ll keep stressing it: the cost of admission for great returns in the stock market is enduring volatility.

NVIDIA is the best U.S. stock of the past decade, but even with perfect foresight into the success of its GPGPU and data center strategy, long-term shareholders had to endure 25%+ drawdowns in 20 of the last 27 years, according to my calculations below (50%+ drawdowns are highlighted in red). The average annual drawdown since NVIDIA went public is -40% and as with any drawdown of 40% or 50%, a fund advisor risks looking foolish in the short-term, external pressures can mount to abandon the right course.

How hard can it be? This became a catchphrase inside NVIDIA to avoid feeling overwhelmed by the work ahead. But the answer to the question is simple: very hard! So hard, in fact, that in a viral clip from his video interview with Acquired, Jensen stated that if he could start the company again, he wouldn’t do it:

“The reason why I wouldn't do it and it goes back to why it's so hard building a company. Building NVIDIA turned out to have been a million times harder than I expected it to be, any of us expected it to be. At that time, if we realized the pain and suffering, and just how vulnerable you're gonna feel, and the challenges that you're gonna endure, the embarrassment, and the shame, and you know the list of all the things that that go wrong… I don't think anybody would start a company. Nobody in their right mind would do it.”

He later clarified that, knowing the outcome, he would of course start NVIDIA again. Yet throughout the entire book, Jensen’s extreme work ethic is a recurring theme. When asked for advice on achieving success, Jensen’s answer was always: “I wish upon you ample doses of pain and suffering.” When employees complained about the long hours at NVIDIA, he replied: “People who train for the Olympics grumble about training early in the morning, too.” And regarding his high standards for his leadership team, he said: “I don’t like giving up on people, I’d rather torture them into greatness”. The takeaway is that it doesn’t matter what you want, but how badly you want it. Achieving anything extraordinary was never meant to be easy.

Did I Enjoy the Book and Would I Recommend It?

Yes, I enjoyed it and think Tae Kim has done a great job, especially for a debut.

This article is a Substack exclusive.

It was not sent to subscribers of my client newsletter (via MailChimp) which skews towards hedge funds, fund-of-funds, HNWI and endowments. QUALIFIED INVESTORS resident or domiciled in Germany can subscribe for this lower frequency but higher detail newsletter here.* (*by clicking the link, you confirm your status as a QUALIFIED INVESTOR).

This document is for informational purposes only. It is no investment advice and no financial analysis. The Imprint applies.