How the European Commission Is Making Google a Worse Product (Again)

Missing Google Maps or Flights in Search? Blame the EC's Digital Markets Act

“Google fu**ing everything up. Not only is Maps not showing in searches, but businesses are harder to find too” writes a disgruntled Google user on Reddit. Another one adds: “This is so annoying! I search for a place and can't see where it is. And the most stupid thing: every search even gives a preview of Google Maps zooming into the place, but it's not clickable... useless!”

Lots of users are annoyed by the design changes Google brought to its Search Engine Results Page (SERP) in Europe and are puzzled why the company would deliberately kill its popular Google Maps and Flights verticals while the Images, News, Videos, Books and Finance verticals are all still presented in an unchanged manner (see below).

The reason for this design change is not that Google completely lost touch with what its users want (i.e. fast and direct access to the information they’re looking for) but instead that Google started complying with the EC’s Digital Markets Act (DMA).

The DMA is in effect for more than a full quarter now. This article zooms in on the general changes it brought to large digital platform operators in the EU, with a particular focus on how it worsens Google Search. It ends with a short conclusion.

What’s the DMA and Who’s Affected by It?

The DMA is a new EU law that regulates large tech companies. Its stated goal is to make markets in the digital sector “fairer” and “more contestable”. It was proposed by the European Commission (EC) in 2020, adopted in 2022 and “gatekeeper” companies had until March 2024 to comply with all of the DMA’s obligations (see below).

“Gatekeepers” are the largest providers of digital core platform services (CPS) in the EU and only they are governed by the DMA. The EC originally designated six firms as gatekeepers: Google, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta, and Microsoft. These are all - surprise! - non-European companies. With the DMA in force, the EC now has a tool to impose fines of up to 10% of total global revenue on these foreign tech giants in case of infringement, which can go up to 20% in case of repeated infringement.

To be designated as a gatekeeper, a platform company must surpass certain criteria. Before being added by the EC to the unpopular list above, a technology firm must:

provide an important core platform service in at least three EU member states,

either have had an annual turnover within the EU of at least €7.5 billion in the last three financial years or have a market valuation of at least €75 billion,

have at least 45 million monthly active end users established or located in the EU - AND -

have at least 10,000 business users established in the EU.

Booking.com is the newest addition to the group. It recently surpassed the thresholds and was designated as the seventh gatekeeper by the EC in May 2024. It received six months to comply with all of the DMA’s obligations by November.

But what exactly are the obligations? And how do they impact a company’s behavior?

If one goes through the full text of the law, one basically ends up with a list of four “Dos” and four “Don’ts”. I’ll break down each of those four in the next section.

The Dos and Don’ts of the DMA

All seven gatekeepers, and only they, must incorporate a comprehensive list of obligations into their conduct. 20+ obligations are laid out in Article 5, 6 and 7 of the DMA. The most important ones can be boiled down to four “Dos” and four “Don’ts”. You can see the four “Dos” below, i.e. what a gatekeeper must allow in the EU:

“Do” number 1 was partly construed to enable interoperability between messaging services. A Signal or Telegram user in the EU shall have the ability to send a message to a WhatsApp user without downloading WhatsApp. The gatekeeper, in this case Meta, must invest to build the necessary APIs for its messengers to interoperate with its direct competitors. Different from the U.S., where iMessage is leading, WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger are the two most popular instant messaging apps in the EU.

“Do” number 4 is another interesting one. It instructs Alphabet and Apple to allow third-party app stores and sideloading on their mobile OS. Sideloading means users shall have the ability to download app installation files directly from the developer’s website and not exclusively through the gatekeeper’s app store. “Do” number 4 prescribes that app developers shall be able to inform their customers of cheaper purchasing options outside the gatekeeper’s CPS, steer them to those offers - free of charge - and allow them to conclude purchases outside the gatekeeper’s own payment service. In short: anti-steering provisions are now forbidden in the EU by law.

This wraps up the four “Dos”. Below, you can see the four “Don’ts”, i.e. what a core platform service provider may no longer engage in:

The list of “Don’ts” starts with a banger. “Don’t” number 1 bans self-preferencing of a gatekeeper’s own offerings in rankings, crawling and indexing which exerts a meaningful adverse impact on Google’s SERP design in the EU. “Don’t” number 3 shall provide users with more choice over default apps. For key services like search engines or web browsers, gatekeepers must present choice screens where their own services are listed alongside smaller competitors. “Don’t” number 4 demands more consent for targeted ads and the DMA also prohibits gatekeepers from combining personal data across several of their own products (i.e. without explicit consent, different Google services like YouTube, Chrome and Search may no longer share your data amongst each other to personalize your ads or your Discover feed).

From Individual EC Decisions to Collective Prohibitions

None of these obligations fell from the sky. The DMA builds to a large extent on historical EC antitrust decisions against individual gatekeepers. Despite some of those decisions being appealed and not considered settled case law, the restrictions are now imposed on all seven gatekeepers collectively.

To give two examples: the DMA’s anti-steering obligations are grounded in the EC’s individual decision against Apple from March 2024 where it fined Apple €1.8 bn because the company’s anti-steering provisions and prohibition of link-outs imposed on music streaming apps were found to be in breach of Article 102(a) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (see the EC’s illustration below).

The DMA’s self preferencing ban is grounded in the EC’s individual decision against Google from June 2017 where it fined Google €2.4 bn for illegally preferencing its own comparison shopping service “Google Shopping” over rivals. The Google Shopping decision can be considered the EC’s original sin in its tech regulation evolution. For the first time, it forced a tech company (Google) to alter its screen design not only for the sake of the company’s own two prior motives, i. e. a) serve users better or b) increase revenues, but to appease a regulator lobbied by a small group of competitors with dated products and dying business models.1 The Google Shopping case is crucial for understanding the doctrinal basis of the DMA’s self-preferencing framework and I will revisit the case further down in this article. Subsequently, I’ll connect the dots how the newest obligations by the EC make Google a worse product in the EU (again).

Before focusing on Google, I’ll go through three important changes that the DMA brought on the other gatekeepers. Three important current battlefields are:

A. Messaging Interoperability

B. Choice Screens and

C. App Stores

A. Messaging Interoperability

Article 7 of the DMA introduces the interoperability requirements for messaging apps amongst others. They sound great in theory, but run into a roadblock in practice as they make it difficult to maintain a uniform level of encryption and feature sets between the sender and receiver of a message. Right now, Article 7 only includes text messaging between individual users and sharing of images, videos and voice messages but its scope shall expand to group functionality and calling in the years ahead.

The gatekeeper most directly impacted here is Meta due to its 2014 acquisition of WhatsApp. WhatsApp messages are end-to-end encrypted (E2EE) since 2016 based on using the Signal protocol. Meta has proposed that smaller competitors like Threema, Signal or Telegram shall use the same protocol to protect messages in transit to WhatsApp’s infrastructure (see the illustration below).2

Since Threema and Signal already use the Signal protocol, onboarding these two players to the liking of the EC should be a no-brainer, right? Wrong! Meredith Whittaker, Signal’s president, expressed no interest at all opting into WhatsApp’s terms of service because:

“of course Signal can’t interoperate with another messaging platform, without them raising their privacy bar significantly, even ones like WhatsApp that support end-to-end encryption and already partly utilize the protocol. Because we don’t just encrypt the contents of messages using the Signal protocol. We encrypt metadata, we encrypt your profile name, your profile photo, who’s in your contact list, who you talk to, when you talk to them. That would need to be the level of privacy and security agreed across the board with anyone we interoperated with before we could consent to interoperate.”

Threema’s CEO, Martin Blatter, shares Whittaker’s reservations around how user metadata would be handed over to WhatsApp. To the best of my knowledge, Telegram also has shown zero interest to partake in WhatsApp’s offer.

In summary, the EC’s messaging interop obligations are going nowhere. Meta had to build an offer. They did. Every other messaging app was free to walk away from it. They did. Even if a competitor chooses to opt in, users must be asked in the next step whether they want to enable third-party chats at all. Given how strongly some Telegram or Threema users disguise Meta, it’s debatable how many would want that. A WhatsApp user opted into third-party chats will receive messages from outside apps in a separate tab and will be explicitly warned that “spam and scams may be more common in third party chats”.

Uniting users from different messaging apps on common ground and common protocols carries unavoidable costs especially after these apps have differentiated their offerings via different privacy levels or feature sets for a decade. Another reason why the EC won’t reach their goals here is much simpler: WhatsApp users are generally happy with the gatekeeper’s service and have no intention to change the status quo.

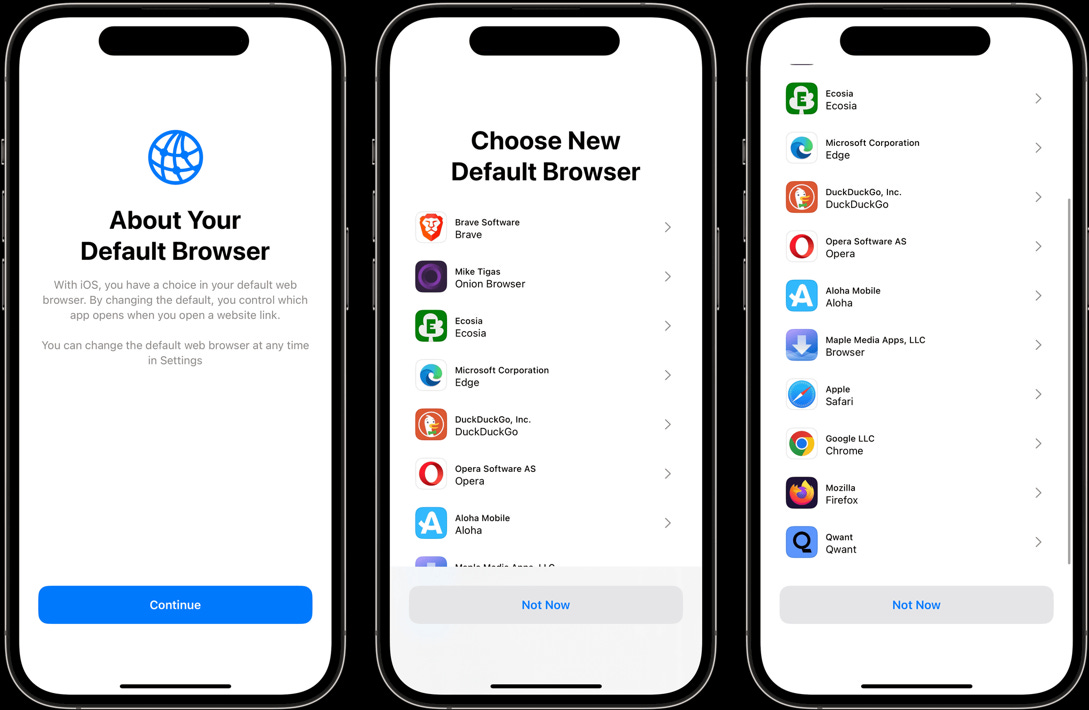

B. Choice Screens

Article 6(3) of the DMA introduces the gatekeepers’ obligations to display choice screens whenever a user first uses a web browser or a search engine. An EU buyer of a new iPhone or Android device must click through one or two new choice screens which are shown later in this article. Article 6(3) reads in full:

“The gatekeeper shall allow and technically enable end users to easily un-install any software applications on the operating system of the gatekeeper, without prejudice to the possibility for that gatekeeper to restrict such un-installation in relation to software applications that are essential for the functioning of the operating system or of the device and which cannot technically be offered on a standalone basis by third parties.

The gatekeeper shall allow and technically enable end users to easily change default settings on the operating system, virtual assistant and web browser of the gatekeeper that direct or steer end users to products or services provided by the gatekeeper. That includes prompting end users, at the moment of the end users’ first use of an online search engine, virtual assistant or web browser of the gatekeeper listed in the designation decision pursuant to Article 3(9), to choose, from a list of the main available service providers, the online search engine, virtual assistant or web browser to which the operating system of the gatekeeper directs or steers users by default, and the online search engine to which the virtual assistant and the web browser of the gatekeeper directs or steers users by default.”

Android complies with Article 6(3) by showing the two choice screens below during the initial setup of a new device. Alternatives for its web browser and search engine are presented besides the gatekeeper’s offerings (Chrome, Google) in random order.

In the case of an iPhone, the mechanism is a bit different. The web browser choice screen below is not shown during the initial setup but when a user first opens Safari.

Given the proliferation of choice screens in Europe, one would assume there’s robust evidence for their effectiveness. In my 2023 Investor Letter, I wrote on the topic: if the goal is that consumers can freely choose their preferred service, it gets the job done nicely. However, if the goal is to alter market shares – which I assume the EC would prefer to see – choice screens do not dent the popularity of the leading product at all.

The new DMA choice screens were introduced in March. Initially, Firefox claimed a 50% increase in users in Germany while Brave allegedly saw a 40% jump in browser installs on iOS. A reality check does not align with the statements though. According to StatCounter, Chrome and Safari commanded a combined browser market share of 90% on all European mobile devices as of June June 2023 (pre-DMA). A year later (post-DMA) their market share stood unchanged at 90% while Firefox even marginally lost market share with 0.93% as of June 2024 compared to 0.97% a year earlier.

Unexpectedly, choice screens don’t sustainably boost user acquisition for subpar alt-browsers. Instead, users remain loyal to the best products while competitors continue to complain to the EC that the regulations are not stringent enough. Take the words of Ecosia founder, Christian Kroll, who spoke to the FT about his fears that “the new rules risk leaving his company worse off than before the rules were in place because Google is still able to offer its own services alongside less familiar alternatives. He has already seen evidence that traffic will go straight to Google. “You can’t assume that someone who has been using Google for 20 years will choose something else,” Kroll says. He adds: “The reason this law was made was to repair the damage done to competition. This is not happening. It might even be damaging us.”

The flaw in this assessment is that sound competition policy shouldn’t strive for equal results but equal opportunity. It's common knowledge that users vote with their clicks whenever a new digital service emerges that is genuinely better than the previous gatekeeper. For example, 75% of Edge users switch their default search engine from Bing to Google because they think Google is better. Between 2005 and 2010, Firefox took share away from Internet Explorer because users thought Firefox was better only to be later overtaken by Chrome once the latter outcompeted the former. Users are not nearly as dumb as competitors regularly want to make the EC believe and equal opportunity (in new choice screens) shouldn’t lead to equal results. As long as the EC considers measuring the DMA’s effectiveness on leveled market shares rather than on increased consumer welfare, more potentially misguided constraints could follow.

C. App Stores

Article 6(4) of the DMA introduces gatekeepers’ obligations to allow sideloading. The most important passage of the Article reads:

“The gatekeeper shall allow and technically enable the installation and effective use of third-party software applications or software application stores using, or interoperating with, its operating system and allow those software applications or software application stores to be accessed by means other than the relevant core platform services of that gatekeeper.”

Next, Article 5(4) states that gatekeepers shall allow app developers to steer already acquired end users - free of charge - towards alternative cheaper offers outside the gatekeeper’s platform and allow them to conclude purchases outside the gatekeeper’s own payment service (that’s IAP in the case of Apple). The Article reads:

“The gatekeeper shall allow business users, free of charge, to communicate and promote offers, including under different conditions, to end users acquired via its core platform service or through other channels, and to conclude contracts with those end users, regardless of whether, for that purpose, they use the core platform services of the gatekeeper.”

To comply with the DMA’s sideloading and anti-steering obligations, Apple introduced a new set of business terms. Developers can now either choose to:

a) stay on the old terms OR

b) adopt the new terms if they want to use any of the alternative distribution or payment methods (see below).

Under the old terms, developers may distribute their iPhone apps only via the App Store, they exclusively must use Apple’s In-App Purchase system (IAP) and they are subject to the standard 30% commission rate (which is lowered to 15% for small businesses or subscriptions after the first year).

The new terms are requisite to use any of the new DMA mandated capabilities. They come with a reduced 17% commission rate (lowered to 10% for small businesses or subscriptions after the first year) and developers no longer must use IAP. However, if they still wish to use IAP, they pay an extra 3% to Apple + the 17%/10% commission.

This equates to a 10PP reduction in commissions or 2PP for small businesses or subscriptions after the first year. The new terms allow developers to distribute their apps via alternative app stores and “eligible” developers may also let users sideload their iPhone apps via direct web distribution. It’s important to note that the new terms do not mean a developer will automatically be excluded from also staying present in the App Store nor from using IAP. This leads to an obvious question: “why wouldn’t every developer immediately switch to the new terms and lower its “Apple tax”?

To recoup potential losses from the reduced commission rate under the new terms, Apple introduced an additional Core Technology Fee (CTF) of €0.50 for each first annual install over one million. It may also charge the CTF when the same user reinstalls the app a year later. For developers with broadly downloaded apps but not a lot of revenue, the fee makes it uneconomical to distribute apps outside of the App Store.3 Should a developer decide to distribute solely through a third party app store, Apple is prohibited from charging that developer a commission except for the CTF. The developer instead must pay a new commission set by the third party app store and the store itself must pay Apple the CTF for every first annual install of its app.

Let’s put all this together using a hypothetical example.

Spotify Example

Due to the new DMA mandated capabilities, a developer like Spotify shall theoretically be allowed to only distribute its app through alternative app stores or sideloading in the EU if it so desires. If Spotify would like to solely enable sideloading and bypass IAP, Apple would still charge it 1) the new annual Core Technology Fee of €0.50 per install over one million (irrespective of whether that install leads to a free or a paying user) plus 2) a 17% commission for each new subscription created through the app.

In a different scenario where Spotify wanted to keep its app inside the App Store but start steering its users to subscribe from within the app solely through its own payment method instead of IAP, the charges would be identical to the terms just described, i. e. the €0.50 CTF per annual install plus a 17% commission for every new subscription generated through Spotify’s own payment method.

Spotify ran the numbers for every possible scenario and concluded that any deviation from the status quo would ”equate for us to being the same or worse as under the old rules.”

Thus, it postponed its planned design changes for the EU depicted below and neither allowed users to subscribe from within the app via its own payment method nor did it show pricing information within the app until August 2024. Regarding the latter, Apple relented on August, 14 and allowed Spotify to include pricing information for its plans in the app (but without a link to conclude purchases bypassing IAP).

Good in Theory, Difficult in Practice

As we have already encountered with the messaging interop obligations or choice screens, the EC’s initiatives to loosen Apple’s grip on the app economy sound good in theory but come with trade-offs in practice. For example, opening up a closed ecosystem like iOS inevitably comes with a lowering in security. In consequence, Apple rolled out a new notarization process where it scans all iOS apps available for alternative distribution methods for security threats but nonetheless it claims that since March:

“Government agencies, both in the European Union and outside of it, have been quick to recognize the risks created by these new distribution options and the need for protective measures. These agencies — especially those serving essential functions such as defense, banking, and emergency services — have reached out to us about these new changes, seeking assurances that they will have the ability to prevent government employees from sideloading apps onto government-purchased iPhones. Several have told us that they plan to block sideloading on every device they manage. One EU government agency informed us that it had neither the funding nor the personnel to review and approve apps for its devices, and so planned to continue to rely on Apple and the App Store because it trusts us to comprehensively vet apps.”

Apple obviously talks its own book here but it’s not without a certain irony, that one executive body, the EC, fought hard to enable alternative distribution methods and other government agencies immediately plan to disable them. Apple’s rebuttal of the new app store rules came in a harsh tone when it concluded that: “sideloading is one of many reasons why in the EU, the DMA’s changes will result in a system that’s less secure than the model we have in place in the rest of the world.”

The reason why Apple fights back so hard is simple: It doesn’t want to endanger its global profit pool of ~$20 bn from App Store commissions, nor does it want the EC’s initiatives to be emulated by U.S. regulators. Thus, the scuffle about the App Store economics resembles a game of cat and mouse. What makes the issue especially challenging, is, that despite the fact that Apple’s take-rates for purchases from already acquired end users appear supra-competitive, it’s not always easy to argue against the firm’s conduct on principle. Apple established the app economy, they eliminated the malware scare from the PC era, they communicated the business terms to developers in advance and didn’t change the rules once the App Store was a multi-billion dollar platform. They rightfully may charge a compensation for letting developers access their IP and as long as regulators accept a market definition of the relevant market as “digital mobile (gaming) transactions”, the App Store is a duopoly with Google Play instead of a monopoly, which makes it nonsensical that an outsider should cap Apple’s take-rate. (Note: I’m fully aware that different market definitions have already led to different regulatory outcomes as in Epic Games v. Google).4

Summing up, the EC’s new app store obligations are going nowhere and the four App Store alternatives which are live in the EU, AltStore PAL, SetApp Mobile, Aptoide game store and Mobivention, all lack proper incentives for consumers or developers to give them a try in my opinion. But no matter what ultimately will come out of:

A. the new Messaging Interoperability Obligations

B. the new Choice Screens or

C. App Store alternatives

…I don’t actually have a big problem with either one of them. Let me break down why.

Harmless vs. noxious obligations

Don’t get me wrong, I’m sure none of the three obligations will achieve the EC’s goals but, at the end of the day, they are harmless. They leave existing tech offerings intact and simply add (irrelevant) new ones. They give consumers more choice but everyone is also free to ignore them. In short: they don’t take anything away from consumers.

What I do have a problem with are noxious DMA obligations that cripple existing products and take functionalities away from consumers. What strikes me as especially flawed is Article 6 banning self-preferencing of a gatekeeper’s own offerings in rankings, indexing and screen design. I already gave a glimpse at the beginning of this article how Google’s compliance with the DMA meant it had to ban its popular Google Maps vertical. What remains is a non-clickable, useless preview of the Maps functionalities previously available. The preview can only be enhanced and minimized but the user can usually no longer interact with it or start route planning (see below).5

This reduced functionality is directly caused by the DMA’s Article 6(5):

“The gatekeeper shall not treat more favourably, in ranking and related indexing and crawling, services and products offered by the gatekeeper itself than similar services or products of a third party. The gatekeeper shall apply transparent, fair and non-discriminatory conditions to such ranking.”

As previously explained, the EC derived this self-preferencing ban from its 2017 Google Shopping decision. It led to Google altering its screen design to appease the EC, albeit with only minor effects on the user experience at the time. Below, I recount the Google Shopping case, analyze the post-decision remedies and ultimately bridge the gap how we ended up with today’s more intrusive screen design prohibitions.

The EC’s Original Sin

The EC fined Google €2.4 bn in 2017 for its self-preferential treatment of its “Google Shopping” vertical. I wrote the following about the decision in April:

“The EC argued displaying Google Shopping results in a rich format, at the top of the search results page whilst demoting rivals to subsequent pages breached EU antitrust law. Reviewing the exclusionary design choice, the EC emphasized how smaller competitors were harmed while the FTC reviewed the same issue in 2013 and weighed the procompetitive justification for Google’s exclusionary conduct under the rule of reason standard. Contrary to the EC, the FTC found that: “While Google’s prominent display of its own vertical search results on its search results page had the effect in some cases of pushing other results “below the fold”, the evidence suggests that Google’s primary goal in introducing this content was to quickly answer, and better satisfy, its users’ search queries by providing directly relevant information.”

The remedy was the following: Google was forced to alter its SERP in Europe for the first time while nothing had to change in the United States. The EC gave Google 90 days to provide competing comparison shopping services (CSSs) equal access to its Shopping results box as a remedy. Since then, if you’re in Europe and search for products, the Shopping Box will contain sponsored listings from many CSSs, no longer just from Google (see the green dotted area below).

CSSs typically live from a spread between the cost-per-click they receive from merchants for directing traffic to them (often ~€0.5) and what it costs them to acquire traffic. Google Shopping used to monetize merchants directly before the EC’s 2017 decision but ever since, it is not allowed for merchants in Europe anymore to bid for Shopping Ads directly without going through a CSS.

Google itself bids for ad placements in Google Shopping as a CSS but the EC demands proof they won’t systematically underprice competitors. Thus, when Google acts as a CSS in Google Shopping, it takes a high take-rate of 20% of the advertiser’s budget compared to an industry standard of ~5%.

For merchants, this makes going through a competing service more attractive, but overall, Google achieved with its remedy that it turned CSS competitors into paying customers. Aggregating their product feeds into the Shopping Box made the product more useful while simultaneously decreasing the odds that users want to visit disaggregated CSSs directly. In sum, the remedy didn’t impair Google’s economic value in Europe.

The decision was nonetheless deeply flawed in my opinion because especially in product design choices, enforcement agencies should lean heavily towards type II errors (i.e. underenforcement) to not chill innovation. Going forward, the DMA could ban Google from displaying its own AI capabilities prominently in a rich format, near the top of its SERP. Per the EC’s logic, this could constitute an illegal form of self-preferencing while the primary design goal would clearly be procompetitive to better satisfy users’ needs.6 Looking forward, the DMA may deprive European Google users from a roll-out of AI Overviews in Search, a new AI Converse vertical etc.

How the DMA Already Worsens Search in Detail

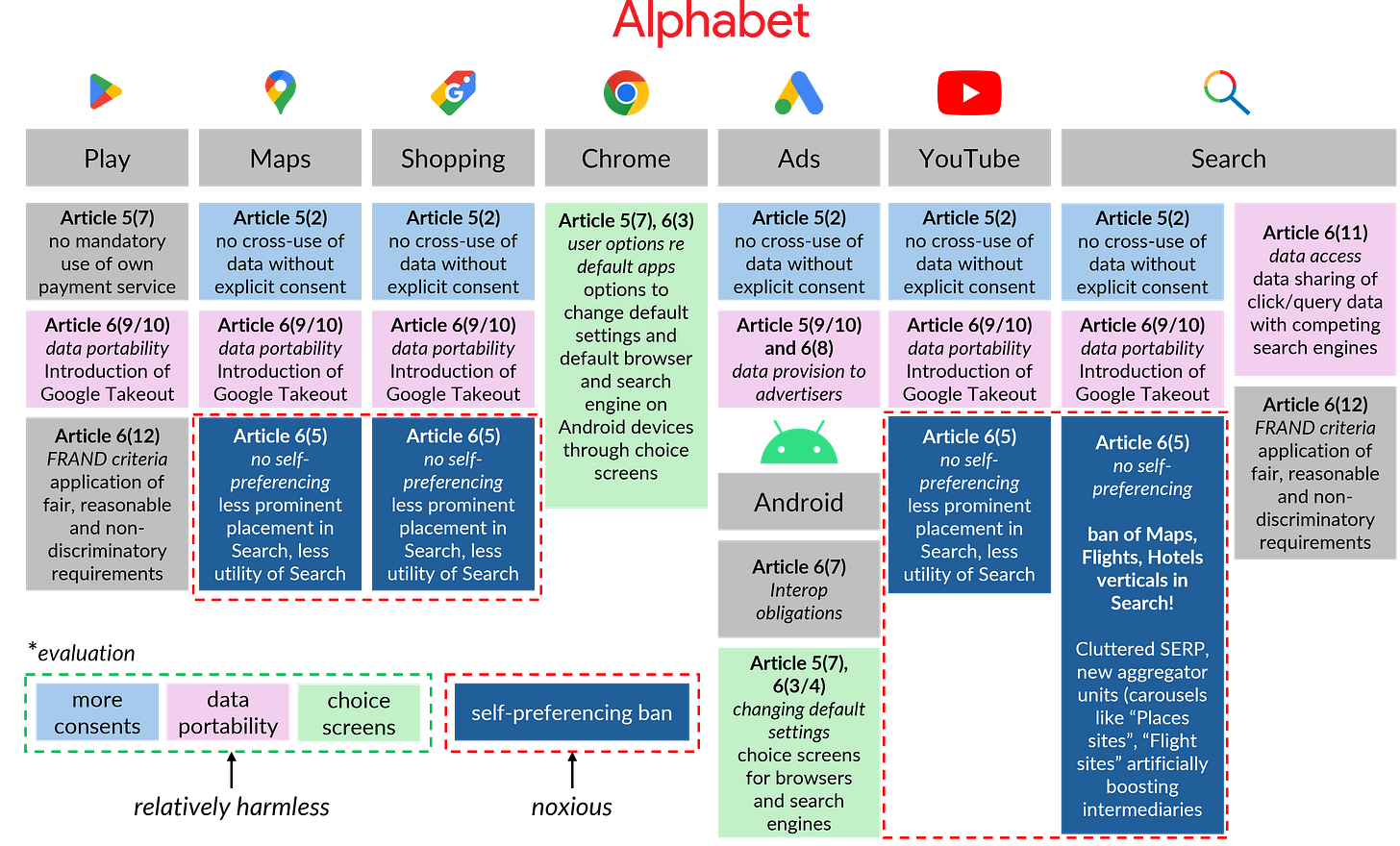

Besides any future impairments of Search, Europeans feel the adverse effects of the DMA already today in their online routines. Below you see an overview of how the DMA impacts each of Alphabet’s CPSs based on an assessment of bureau Brandeis.

Per the EC, Google’s parent company provides eight CPS, the most of any gatekeeper. These are: 1. Play, 2. Maps, 3. Shopping, 4. Chrome, 5. Ads, 6. Android, 7. YouTube and - most importantly - 8. Search. Many of the DMA-induced remedies shown below are annoying (like ever more consent buttons) but ultimately harmless. In contrast, the self-preferencing ban noticeably lowers the utility of Search already today and deprives users of fast access to popular Google verticals.

With the ban of Google’s own verticals in Search7, some unintended second-order effects are starting to surface. Instead of its own offerings, Google must show something else at the top of its page and it made clear what that is:

“When you are searching for something like a hotel, or something to buy, we often show information to help you find what you need, like pictures and prices, as part of our results. Sometimes this can be as part of a result for a single business like a hotel or restaurant, or sometimes it can be a featured group of relevant results. Over the coming weeks in Europe, we will be expanding our testing of a number of changes to the search results page. We will introduce dedicated units that include a group of links to comparison sites from across the web, and query shortcuts at the top of the search page to help people refine their search, including by focusing results just on comparison sites. For categories like hotels, we will also start testing a dedicated space for comparison sites and direct suppliers to show more detailed individual results including images, star ratings and more. These changes will result in the removal of some features from the search page, such as the Google Flights unit.”

To appease the EC, Google created new dedicated spaces for third-party comparison sites and OTAs displayed near the top of the page. A search for “hotels in Berlin”, will generate a SERP with ads at the top, followed by a new carousel (“Websites zu Orten”, in english:”Places sites”) where Google must present several hotel comparison sites as its first organic result (see below).

A search for “flight from berlin to london”, will no longer lead the user to the fully functioning Google flights vertical with a direct overview of relevant listings but instead to another carousel (“Websites zu Flügen”, in english: “Flight sites”). The carousel appears as the top organic search result and highlights, free of charge, non-Google properties in the flight comparison space like Skyscanner or Kayak (see below).

It’s obvious: no user wants this.

A user looking for flights wants to see an overview of available flights instantly. If he had wanted to see a list of flight comparison sites instead, he would have typed “flight comparison sites” into his keyboard and Google would have happily answered that query as well. The stated goal of Article 6(5) is to enhance the user experience and force design choices on gatekeepers which reflect the user preferences. However, in reality, users now must do a lot more clicking to eventually get what they want and Google’s results page looks cluttered for local, shopping, jobs and travel related searches. Thus, the DMA takes speed and user friendliness away from the consumer which I think is bad.

Google’s Internal Review of Its DMA Remedies

Google gave an unfiltered review of how it thinks its DMA compliance is going so far. It should be read as a warning to U.S. policymakers to not make the same mistakes as the EU if the country wants to stay the undisputed leader in tech:

“We’ve always been focused on improving Google Search to help people quickly and easily find what they’re looking for. We developed Google Images to show a photo instead of just a link to a photo. We launched Google Maps to help you find a local business, not just websites that mention its address. And we developed ways to make it easy for people to directly connect with airlines, hotels, and merchants, saving time and money. These features also help a lot of independent companies, including small businesses, compete with large, successful websites.

Rules that roll back some of these advances represent a fundamental shift in competition policy. We encourage other countries contemplating such rules to consider the potential adverse consequences — including those for the small businesses that don’t have a voice in the regulatory process.

We’ll continue to be transparent about our DMA compliance obligations and the effects of overly rigid product mandates. In our view, the best approach would ensure consumers can continue to choose what services they want to use, rather than requiring us to redesign Search for the benefit of a handful of companies.”

But it’s not only the users who are worse off, the DMA also hurts the bottom line of European airlines and hoteliers. That’s because despite Google being known for its aggressive ad expansion, a large part of the traffic from Google Flights and Hotels to airlines and hotel providers is free. Google Flights stopped charging its content partners referral fees in 2020 and while hotel providers can still run ad campaigns in Google Hotels on a CPC basis, basic inclusion and visibility in Google’s Hotel vertical including a free direct booking link is provided free of charge (see below).

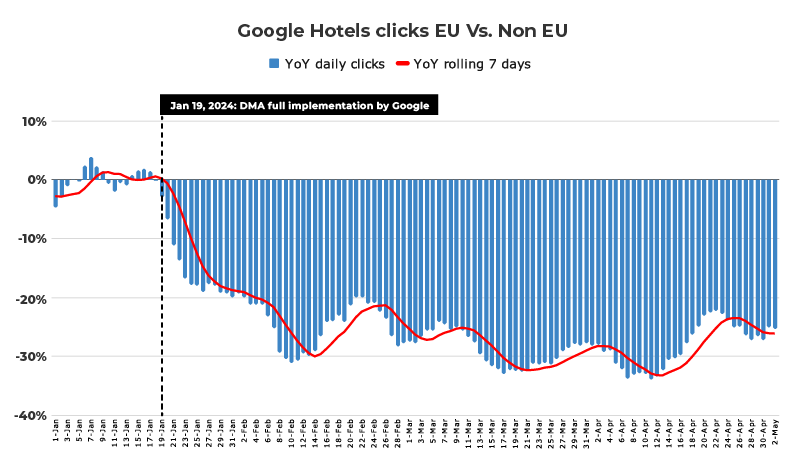

Google began hiding its Hotels vertical in the EU on January 19, 2024. Over the next four months, Mirai, a booking engine and metasearch connectivity provider, analyzed traffic data for 3,450 hotels and found that clicks from Google Hotels ad campaigns in the EU declined 17% while they continued their double-digit growth trend outside of the EU. In sum, Mirai found a -30% Google Hotel ads click differential in the EU vs. non DMA affected markets (see below). This stems from Google Hotels being no longer featured directly in Search and one can assume that free traffic from Google’s free booking links declined in the same magnitude as ad clicks.

Google is aware of this problem and understands how the DMA-induced changes affect free traffic to hotel providers and airlines:

“Under the DMA, we’ve had to remove useful Google Search features for hotels, flights and local businesses […] This benefits a small number of online travel aggregators, but harms a wider range of airlines, hotel operators and small firms who now find it harder to reach customers directly […] These businesses now have to connect with customers via a handful of intermediaries that typically charge large commissions, while traffic from Google was free.”

Booking demand, however, has not changed on absolute basis, so it begs the question: “Who is profiting from all this and absorbs Google Hotel’s booking share loss in the EU?”

The answer is straightforward: The new carousel rich results for flights (Flight sites), hotels or local (Places sites), jobs (Jobs sites) and shopping queries (Product sites) have taken over the space previously reserved for Google’s own verticals and benefit only a handful of competing aggregators. For example, the new unit for hotel searches will regularly highlight, with pictures and free of charge, a link to Booking.com or Expedia.

Therefore, OTAs like Booking.com and Expedia should be the current winners. Instead of Google’s own verticals driving users to purchase directly from airlines or hotel providers, the DMA related remedies artificially boost intermediaries. At this point of the article, it shouldn’t surprise you that Booking.com and Expedia are two leading members of “EU Travel Tech”, a lobbying group which has urged the EC for years to enforce a self-preferencing ban to boost their competitive positioning vis-à-vis Google. Despite the new Search formats benefitting their OTA business since March, the group remains outspoken that they still expect the EC to go harder after Google and request an even more prominent placing of their own offerings in Search while Google shall stop showing even the shrunk-down previews of its own offerings.

Competition Not Competitors

Outside of Europe, it’s often said that U.S. regulators and antitrust laws protect competition while the EC protects individual competitors following an ideology of economic structuralism. How much the EC’s decisions benefit competitors instead of competition is up for debate but the EC’s chairwoman may do herself no favor when she emphasizes how she especially wants direct competitors of the gatekeepers inside her “Team DMA” and counts on them to stay “actively included in monitoring compliance with the DMA” as in one of her recent speeches, quoted below:

“Looking around the room, I see innovators, SMEs, and competition law enforcers from across the European Union. I like to think of us as Team DMA. Because it is going to take teamwork to make the Digital Markets Act a success.

[…] This brings me to the third advantage for SMEs, which is that they are actively included in monitoring compliance with the DMA. We involve consumers, small businesses, and civil society groups in the dialogues we have with the Big Tech firms. Some of you may have attended the compliance workshops we have organised. We need your input to ensure that the DMA is working as intended and benefits everyone. The more you speak up about your market problems, the easier it is for us to enforce the rules. And the more likely it will be that the gatekeepers accept compliance as the only logical option.

Because the ball is now in the gatekeepers' court. They have to convince us that the measures they take will achieve full compliance with the DMA. And where this is not the case, we will intervene.”

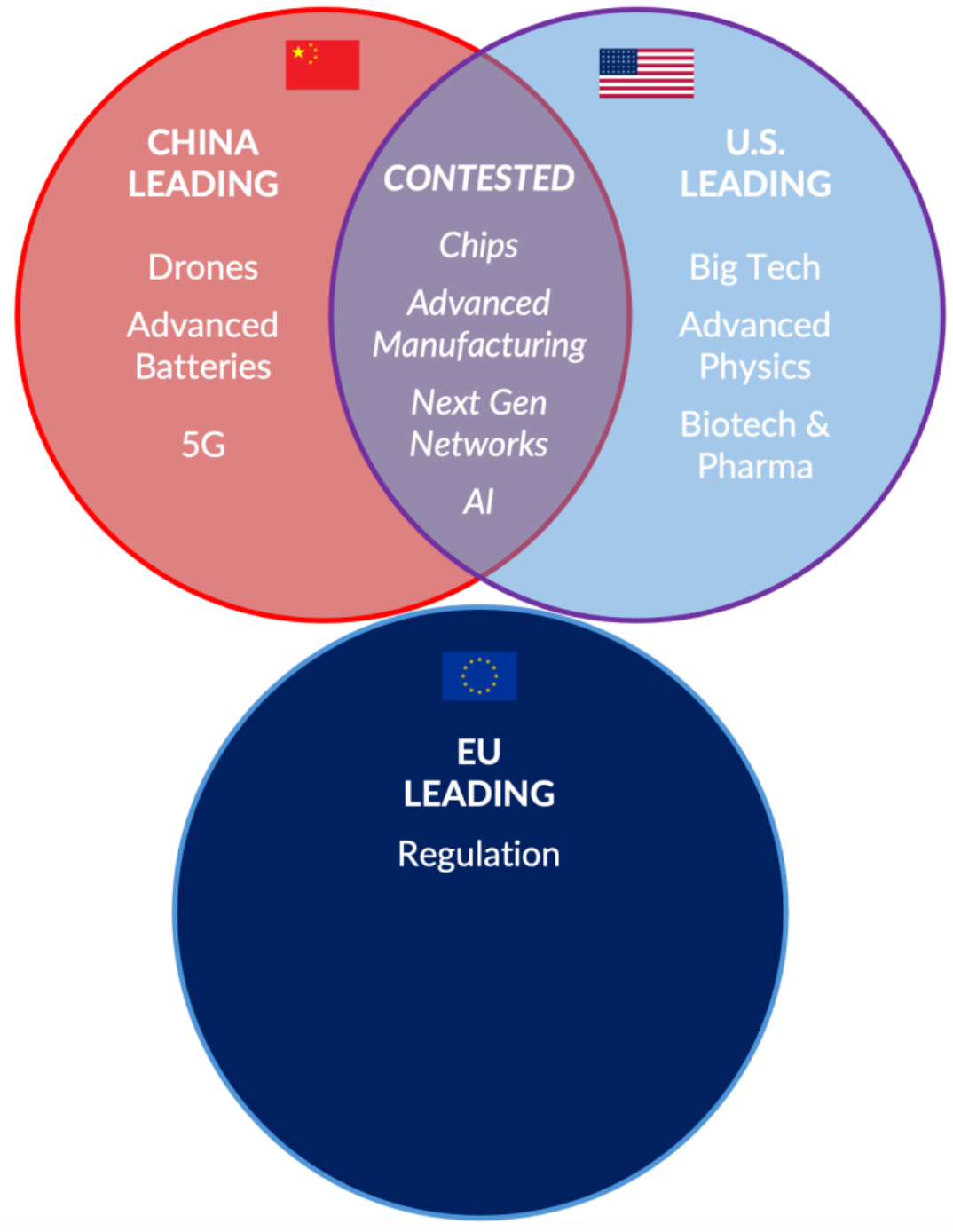

I find it instinctively repelling to join in the belittling of the EU which seems to be en vogue at the moment. However, the EC is doing its fair share to support the consensus view that some of its recent initiatives go too far and will have unintended consequences. Even the main authors of its newest laws like the AI Act must admit by now that “the regulatory bar maybe has been set too high” and insiders recount a prevalent inclination in Brussels to keep adding regulation rather than subtracting it. They also perceive a lack of first-hand understanding of how tech startups operate.

In a great recent article, Stratechery’s Ben Thompson remarked that “European regulators don’t seem to care about incentivizing innovation, and are walking down a path that seems likely to lead to de facto continentalization of private property.” Unfortunately, that’s precisely where the EC is headed as it increasingly finds comfort in its self-assumed role as the global tech regulator. In the short run, this role may have charm for EC bureaucrats but it may cost the entire continent dearly in the long run. With fines now calculated as % of worldwide turnover, it’s only matter of time before the EC overplays its hand and Big Tech stops accepting these fine as just a cost of doing business in the EU, where they earn less than 10% of their total revenue.8

Below I begin the final part of this article where I provide a legal contextualization of the DMA and demonstrate how it differs from traditional antitrust enforcement. I also discuss the EC’s initial non-compliance investigations from March 2024, focusing on why the scrutiny of Apple’s ongoing anti-steering practices is the most interesting case to follow. Thereafter, I close with a short conclusion.

Legal Contextualization Of the DMA

In April, I wrote: “significant changes to a gatekeeper’s conduct are more likely to come from governments passing new laws than antitrust watchdogs enforcing old ones, contingent on a societal consensus whether action is needed at all.” The DMA is a good example that this is true and the law came with the promise to speed up enforcement procedures.9

Antitrust enforcement is a slow, reactive approach and tries to sanction anticompetitive behavior after the infringement has already happened. The DMA shall serve as a proactive approach which prohibits misbehavior ex ante. The law came with the requirement that all seven gatekeeper companies must publish an annual compliance report (the 211 p. strong Google report can be downloaded here). These reports shall streamline the efforts of the EC to detect any infringements and outsource some preliminary investigative work from the EC to the gatekeepers.

With its detailed obligations and gatekeepers having to prove compliance, the DMA was meant to be self-enforcing. But if that’s the case it will lead to a nuisance for the EC, namely that it won’t be able to pocket any money from fines. The money lies in the infringements, not in gatekeepers’ compliance. Therefore - surprise! - just 18 days after the DMA came into application, the EC opened not one, not two, not three, not four, but five non-compliance investigations targeting Alphabet, Apple and Meta.

Non-Compliance Investigations

The EC opened its investigations in March 2024 because it suspected that the suggested solutions put forward by Alphabet, Apple and Meta do not fully comply with the DMA. In detail, it raised doubts:

whether Alphabet’s measures to no longer self-preference Google Flights, Google Shopping or Google Hotels in Search go far enough and are in compliance with Article 6(5). The EC also voiced additional concerns that Alphabet still engages in anti-steering pertaining to the Android Play Store,

whether Apple’s measures in relation to Article 5(4) are in breach of the law, as the Article requires to allow app developers to steer consumers to offers outside the App Store, free of charge. The EC also worries about Apple’s design of its web browser choice screen on the iPhone,

whether Meta’s “pay-or-consent” model for users in the EU complies with the DMA obligation under which gatekeepers must obtain consent from users when they intend to combine or cross-use their personal data.

Apple Preliminarily Found Guilty

In June 2024, the EC preliminarily found Apple guilty. It informed Apple of its view that the App Store rules are in breach of the DMA, since they prevent app developers from freely steering consumers to alternative offers. Apple now has the possibility to defend itself by examining the investigation documents and replying in writing to the preliminary findings. If the EC finds Apple’s defense unconvincing and the App Store rules remain unchanged, it will confirm its preliminary findings in a final decision. Afterwards, it may impose a fine of up to 10% of Apple’s worldwide turnover (i. e. 10% of almost $400 bn). This decision will be made within 12 months from the start of the investigation, i. e. until March 2025.

Coupled with the release of its preliminary findings, the EC opened an additional investigation into Apple’s new contractual terms for developers as a condition to access the new capabilities mandated by the DMA. This investigation will scrutinize:

Apple's Core Technology Fee, under which developers of third-party app stores and third-party apps must pay a €0.50 fee per installed app,

Apple's multi-step user journey to download and install alternative app stores or apps on iPhones (aka the scare screens) and

the eligibility requirements for developers related to the ability to offer alternative app stores or directly distribute apps from the web on iPhones, such as the “membership of good standing” in the Apple Developer Program.

In July 2024, the EC also preliminarily found Meta’s “pay-or-consent” model to be in breach of Article 5(2) of the DMA, under which gatekeepers must seek users' consent for combining personal data between different services, and if a user refuses such consent, they should have access to a less personalised but equivalent alternative.

Up to now, Meta has only provided a new ads free version of its social networks for €12.99/month or the traditional, free version, with a lot of personalised ads. The EC’s rebuttal of Meta’s proposed “pay-or-consent” model is a head scratcher because anybody who understands digital advertising knows that non-targeted ads sell for a fraction of the value of targeted ads. Therefore, it is unclear how Meta shall comply with Article 5(2) if it wants to defend its bottom line in the EU but can’t recoup the revenue shortfall from a less personalised app by charging users a fee.

As of the time of writing, the preliminary findings regarding Google’s non-compliance investigation have not been released yet.

Will Apple Be Forced to Grant Access to Its IP for Free?

Out of all current non-compliance investigations, the final decision regarding Apple’s alleged violation of the DMA’s anti-steering obligations will be the most interesting one to follow. There is an interesting U.S. precedent on the matter from 2021 when Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers ruled in favor of Apple in the antitrust trial EPIC Games v. Apple but with a single restriction that Apple was no longer allowed to continue its anti-steering practices. The Verge summarized the decision as follows:

“As a reminder, this whole case got started when Epic challenged Apple’s up to 30 percent fees to developers for in-app purchases through a splashy campaign where it basically ignored Apple’s App Store guidelines and put in its own mobile payment processing system in its popular game Fortnite. That got the Fortnite app kicked off of the App Store, setting up the perfect scenario for Epic to sue Apple over its rules. Apple filed a countersuit, accusing Epic of breaching its contract.

Ultimately, Gonzalez Rogers found that Epic did breach its contract with Apple with its stunt and ordered it to pay Apple 30 percent of the revenue collected through its outside payment system — about $3.5 million.

Though Apple won on most counts, Gonzalez Rogers also ordered the company to allow developers to use other purchase mechanisms besides Apple’s for in-app purchases. After the Supreme Court declined to take up both Epic and Apple’s appeals earlier this year, Apple was forced to implement this change.”

As of today, Apple must allow developers to steer users from within the app to alternative offers with cheaper prices outside the app and allow users to complete purchases without exclusively using IAP - in both(!) the EU and the U.S.

However, there seems to be one important difference: Judge Gonzalez Rodgers explicitly mentioned the possibility that Apple charges a commission for purchases completed on external websites even if developers bypass IAP and utilized another payment processor:

“First, and most significant, as discussed in the findings of facts, IAP is the method by which Apple collects its licensing fee from developers for the use of Apple’s intellectual property. Even in the absence of IAP, Apple could still charge a commission on developers. It would simply be more difficult for Apple to collect that commission.

In such a hypothetical world, developers could potentially avoid the commission while benefitting from Apple’s innovation and intellectual property free of charge. The Court presumes that in such circumstances Apple may rely on imposing and utilizing a contractual right to audit developers annual accounting to ensure compliance with its commissions, among other methods. Of course, any alternatives to IAP (including the foregoing) would seemingly impose both increased monetary and time costs to both Apple and the developers.

Indeed, while the Court finds no basis for the specific rate chosen by Apple (i.e., the 30% rate) based on the record, the Court still concludes that Apple is entitled to some compensation for use of its intellectual property. As established in the prior sections, see supra Facts §§ II.C., V.A.2.b., V.B.2.c., Apple is entitled to license its intellectual property for a fee, and to further guard against the uncompensated use of its intellectual property. The requirement of usage of IAP accomplishes this goal in the easiest and most direct manner, whereas Epic Games’ only proposed alternative would severely undermine it. Indeed, to the extent Epic Games suggests that Apple receive nothing from in-app purchases made on its platform, such a remedy is inconsistent with prevailing intellectual property law.”

The DMA’s text strikes a somewhat different chord though. It can be interpreted in a way that developers should be able, free of charge, to inform their customers of alternative cheaper purchasing possibilities, steer them to those offers and allow them to make purchases. While the EC explicitly mentions that Apple has the right to charge developers for the initial acquisition of a new paying customer through an iOS app (irrespective of whether the developer uses IAP or a different payment service provider), Article 5(4) could imply that customers with an already existing business relationship with the developer shall be able to conclude incremental purchases without Apple charging a new commission on transactions if the developer forgoes IAP. The original wording of Article 5(4) is:

“The gatekeeper shall allow business users, free of charge, to communicate and promote offers, including under different conditions, to end users acquired via its core platform service or through other channels, and to conclude contracts with those end users, regardless of whether, for that purpose, they use the core platform services of the gatekeeper.”

Article 5(5) only adds to the ambiguity: It requires Apple to let users access digital content acquired outside of IAP inside their respective iOS app. However, this time the article doesn’t mention that the gatekeeper has to allow this access “free of charge” different from Article 5(4) quoted above. Article 5(5) reads in its original form:

“The gatekeeper shall allow end users to access and use, through its core platform services, content, subscriptions, features or other items, by using the software application of a business user, including where those end users acquired such items from the relevant business user without using the core platform services of the gatekeeper.”

To make the confusion complete, the EC stated in its preliminary findings from June 2024 - where it found Apple was in breach of Article 5(4) - that the 17% commission Apple charges if users click on an External Purchase Link and conclude a purchase without using IAP is too high for their taste:

“Whilst Apple can receive a fee for facilitating via the App Store the initial acquisition of a new customer by developers, the fees charged by Apple go beyond what is strictly necessary for such remuneration. For example, Apple charges developers a fee for every purchase of digital goods or services a user makes within seven days after a link-out from the app.”

This whole ambiguity leads to a big question of principle, namely if the DMA mandates Apple to give away access to its IP for free whenever an already-acquired customer of a developer engages in follow-up transactions. How much Apple may charge for distribution methods ex IAP is concurrently also debated in the U.S., where EPIC and Apple are back in court to find out whether the 27% commission for transactions ex IAP in the U.S. is in compliance with the 2021 court order or not.

In the U.S., Apple sought to comply with the court’s 2021 permanent anti-steering injunction in the following way: It allowed developers to tell users about digital goods offerings outside of Apple’s payment system and even include buttons with external purchase links. However, in that case Apple feels entitled to a 27% vs. a prior 30% commission for transactions that take place on a developer’s website within seven days after a user taps through an External Purchase Link. Developers who use a third-party payment processor will need to pay it an extra ~3% of the value while the up to 27% take-rate is the same commission policy Apple already implemented in the Netherlands, where the local competition watchdog ordered Apple to let dating apps use third-party payment processors within their apps:

“To comply with an order from the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM), developers distributing dating apps on the Netherlands App Store can choose to do one of the following: 1) continue using Apple’s in-app purchase system, 2) use a third-party payment system within the app, 3) include an in-app link directing users to the developer’s website to complete a purchase, or 4) use a third-party payment system within the app and include a link directing users to the developer’s website to complete a purchase.

[…] Consistent with the interim relief ruling of the Rotterdam district court, dating apps that are granted an entitlement to link out or use a third-party in-app payment provider will pay Apple a commission on transactions. Apple will reduce its commission by 3% on the price paid by the user, net of value-added taxes. This is a reduced rate that excludes value related to payment processing and related activities.”

Based on historic precedents, Judge Gonzalez Rogers may not want to move in the same direction as the EC, i.e. dictate prices to a company in a market where it ruled that Apple wasn’t even a monopolist. In the EU, meanwhile, Apple’s anti-steering non-compliance investigation clearly shows that the scope of the DMA, and how it impacts gatekeepers’ pricing and business model decisions, is in flux and will be refined through the upcoming decisions and remedies. With Apple currently testing the limits of the law, researchers of the Institute of Commercial and Economic Law correctly synthesized that the way to final ex ante compliance will be long:

“The DMA should be largely self-enforcing due to a high degree of detail in the regulation. It could be doubted whether this goal can be achieved if three major investigations have to be opened within a month of the end of the implementation phase; and even more proceedings are in the pipeline. This could be a sign that the implementation of the ex-ante rules in the DMA alone is not sufficient to fundamentally change the behaviour of the gatekeepers. The gatekeepers seem (still) to consciously test the limits of the law. This does not necessarily mean that the regulation by the DMA is faulty because the behaviour of the gatekeepers can also simply stem from the fact that the DMA hits the core of their business activities. Thus, the gatekeepers have an extremely high incentive to fight for every conceivable aspect of their business model instead of voluntarily giving some parts of it up as this would mean foregoing considerable profit prospects. Therefore, it can be stated that at the substantive level, only a quick conclusion of the non-compliance investigations now initiated would bring real added value. Every concluded non-compliance investigation will help in clarifying the scope of the regulation. Increased clarity might ultimately induce gatekeepers to (final) ex-ante compliance.”

Conclusion

In this article, I showed how the EC’s DMA is making Google a worse product in the EU vs. elsewhere. Should the local regulatory environment not change, a transatlantic bifurcation in the quality of tech services appears likely. This is not a hypothetical: Apple has announced to hold back Apple Intelligence in the EU because of the DMA’s interoperability requirements. Meta won’t release its new foundational models in the EU over the coming months due to “the unpredictable nature of the European regulatory environment”. Meta’s “Threads” became the fastest app to reach 100m users in July 2023 just 5 days after its launch. However, EU citizens had to wait half a year to try out the service as Meta needed to figure out how to comply with the DMA. One may think each of these non-launches is irrelevant in itself but the collective unintended second-order effects of the EU slowly falling behind and engineers not being able to build on top of the most cutting-edge technology may not be.

In the end, every successful tech company operates the same business model: build once, sell often. High costs to build a separate offering for the EU may not be worth the effort. Some might think domestic startups will stand ready to seize any new opportunities if foreign ones no longer enter (as happened behind China’s Great Firewall). However, make no mistake: this is highly unlikely as the European Single market has plenty of cultural, legal, tax, currency and language barriers, non-existent to the same degree in the U.S. or China. The Old Continent’s idiosyncrasies make it challenging to build a tech platform once and then sell often, which is why the EU has almost no globally relevant consumer platforms. Some forecasts see AI adding >1PP to annual GDP growth. It seems illusory if local rulemakers believe it will be enough to just tax this future growth instead of actively participating in its creation.

Holdings Disclosure: At the time of writing, the fund I initiated and advise holds a position in Alphabet at an average cost of $113 per share.

[end of post]

If you don’t want to miss anything, you can follow me on Twitter: patient_capital

To learn more about the investment fund I advise or access my previous annual letters to investors you can visit: https://www.patient-capital.de/fonds

This document is for informational purposes only. It is no investment advice and no financial analysis. The Imprint applies.

Comparison shopping services (CSSs) came under pressure from ever more people starting their product searches directly on Amazon.

Different compatible protocols are eligible if they can demonstrate the same security guarantees as Signal.

Apple later clarified that it won’t charge small developers the CTF when their app suddenly goes viral but the the developer earns less than €10m.

Market definition - the most important question in any antitrust case - paved the way for why, on the one hand, EPIC suffered a near-complete defeat in its 2020 lawsuit against Apple and while, on the other hand, EPIC won its case against Google at a different court which followed a narrow market definition of “Android app distribution” which logically made the Play Store a monopoly.

Google is at times testing a compromise solution where it shows a route planning button that links to Google Maps but the Maps vertical itself is permanently banned.

The DMA’s self preferencing ban in Article 6(5) DMA disallows gatekeepers to make any arguments on the basis of procompetitive justifications for their behavior. Whether self-preferencing increases consumer welfare is irrelevant in regard to how the DMA applies.

Google Search users in the EU have lost direct and fast access to the Google Maps and Flight offerings. Since March, they must go to Google’s Travel offering separately.

Apple has disclosed that 7% of its total App Store revenues stem from the EU which could be a good proxy for its overall revenues in the region. Meta’s EU revenues are 10% of its total revenues.

As a point of reference regarding the procedural length of traditional antitrust enforcement: The EC’s Google Shopping decision stems from a 2009 complaint by shopping comparison competitor Foundem, and the formal investigation began in 2010. The EC ruled against Google in 2017 and Google appealed the decision. In 2021, the ruling was upheld and Google subsequently escalated the appeal to the European Court of Justice, the EU’s highest court, with a final verdict expected in the coming months. It appears that the EC’s decision will be confirmed which implies that a final verdict will be issued 14(!) years after the initial investigation began in 2010.

Hey, great job on the detailed article. Excellent analysis. I wrote about a related topic recently (https://loeber.substack.com/p/20-no-more-eu-fines-for-big-tech) with the same overarching concerns as in your conclusion. My view is that the EC is overplaying their hand with their fines and regulatory environment -- big tech companies like Google provide useful services to consumers, and consumers will rebel once they realize that these abstract regulations are depriving them of real things of value.

If not that, then I fear we will see a bifurcation of technical products available, which could be a tremendous loss for European citizens as we're moving into an AI boom. If Apple and Meta won't release their latest AI products in the EU, then it prevents European technologists from building on those technologies, and that's a *compounding* loss of competitiveness. The consequences downstream of this are measured not just in GDP, but in quality of life and -- looking at AI as it intersects with healthcare, for example -- in lives.